Estude fácil! Tem muito documento disponível na Docsity

Ganhe pontos ajudando outros esrudantes ou compre um plano Premium

Prepare-se para as provas

Estude fácil! Tem muito documento disponível na Docsity

Prepare-se para as provas com trabalhos de outros alunos como você, aqui na Docsity

Os melhores documentos à venda: Trabalhos de alunos formados

Prepare-se com as videoaulas e exercícios resolvidos criados a partir da grade da sua Universidade

Responda perguntas de provas passadas e avalie sua preparação.

Ganhe pontos para baixar

Ganhe pontos ajudando outros esrudantes ou compre um plano Premium

Comunidade

Peça ajuda à comunidade e tire suas dúvidas relacionadas ao estudo

Descubra as melhores universidades em seu país de acordo com os usuários da Docsity

Guias grátis

Baixe gratuitamente nossos guias de estudo, métodos para diminuir a ansiedade, dicas de TCC preparadas pelos professores da Docsity

Arduino e ferramentas

Tipologia: Notas de estudo

1 / 130

Esta página não é visível na pré-visualização

Não perca as partes importantes!

by Massimo Banzi

Copyright © 2011 Massimo Banzi. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A.

Published by Make:Books, an imprint of Maker Media, a division of O’Reilly Media, Inc. 1005 Gravenstein Highway North, Sebastopol, CA 95472

O’Reilly books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For more information, contact our corporate/institutional sales department: 800-998- or corporate@oreilly.com.

Print History: October 2008: First Edition September 2011: Second Edition

Executive Editor: Brian Jepson Designer: Brian Scott Indexer: Ellen Troutman Zaig Illustrations: Elisa Canducci with Shawn Wallace

The O’Reilly logo is a registered trademark of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The Make: Projects series designations and related trade dress are trademarks of O’Reilly Media, Inc. The trademarks of third parties used in this work are the property of their respective owners.

Important Message to Our Readers: Your safety is your own responsibility, including proper use of equipment and safety gear, and determining whether you have adequate skill and experi- ence. Electricity and other resources used for these projects are dangerous unless used properly and with adequate precautions, including safety gear. Some illustrations do not depict safety precautions or equipment, in order to show the project steps more clearly. These projects are not intended for use by children.

Use of the instructions and suggestions in Getting Started with Arduino is at your own risk. O’Reilly Media, Inc., and the author disclaim all responsibility for any resulting damage, injury, or expense. It is your responsibility to make sure that your activities comply with applicable laws, including copyright.

ISBN: 978-1-449- [LSI]

Preface

A few years ago I was given a very interesting

challenge: teach designers the bare minimum

in electronics so that they could build inter-

active prototypes of the objects they were

designing.

I started following a subconscious instinct to teach electronics the same way I was taught in school. Later on I realised that it simply wasn’t working as well as I would like, and started to remember sitting in a class, bored like hell, listening to all that theory being thrown at me without any practical application for it.

In reality, when I was in school I already knew electronics in a very empirical way: very little theory, but a lot of hands-on experience.

I started thinking about the process by which I really learned electronics:

of them and seeing what happened to the device: usually something between an explosion and a puff of smoke.

that I found in magazines to make them do new things.

As a little kid, I was always fascinated by discovering how things work; therefore, I used to take them apart. This passion grew as I targeted any unused object in the house and then took it apart into small bits. Even- tually, people brought all sorts of devices for me to dissect. My biggest

Preface v

vi Getting Started with Arduino

projects at the time were a dishwasher and an early computer that came from an insurance office, which had a huge printer, electronics cards, magnetic card readers, and many other parts that proved very interesting and challenging to completely take apart.

After quite a lot of this dissecting, I knew what electronic components were and roughly what they did. On top of that, my house was full of old electronics magazines that my father must have bought at the beginning of the 1970s. I spent hours reading the articles and looking at the circuit diagrams without understanding very much.

This process of reading the articles over and over, with the benefit of knowledge acquired while taking apart circuits, created a slow virtuous circle.

A great breakthrough came one Christmas, when my dad gave me a kit that allowed teenagers to learn about electronics. Every component was housed in a plastic cube that would magnetically snap together with other cubes, establishing a connection; the electronic symbol was written on top. Little did I know that the toy was also a landmark of German design, because Dieter Rams designed it back in the 1960s.

With this new tool, I could quickly put together circuits and try them out to see what happened. The prototyping cycle was getting shorter and shorter.

After that, I built radios, amplifiers, circuits that would produce horrible noises and nice sounds, rain sensors, and tiny robots.

I’ve spent a long time looking for an English word that would sum up that way of working without a specific plan, starting with one idea and ending up with a completely unexpected result. Finally, “tinkering” came along. I recognised how this word has been used in many other fields to describe a way of operating and to portray people who set out on a path of explora- tion. For example, the generation of French directors who gave birth to the “Nouvelle Vague” were called the “tinkerers”. The best definition of tinkering that I’ve ever found comes from an exhibition held at the Exploratorium in San Francisco:

Tinkering is what happens when you try something you don’t quite know how to do, guided by whim, imagination, and curiosity. When you tinker, there are no instructions—but there are also no failures, no right or wrong ways of doing things. It’s about figuring out how things work and reworking them.

viii Getting Started with Arduino

This book is dedicated to Luisa and Alexandra.

First of all I want to thank my partners in the Arduino Team: David Cuartielles, David Mellis, Gianluca Martino, and Tom Igoe. It is an amazing experience working with you guys.

Barbara Ghella, she doesn’t know, but, without her precious advice, Arduino and this book might have never happened.

Bill Verplank for having taught me more than Physical Computing.

Gillian Crampton-Smith for giving me a chance and for all I have learned from her.

Hernando Barragan for the work he has done on Wiring.

Brian Jepson for being a great editor and enthusiastic supporter all along.

Nancy Kotary, Brian Scott, Terry Bronson, and Patti Schiendelman for turning what I wrote into a finished book.

I want to thank a lot more people but Brian tells me I’m running out of space, so I’ll just list a small number of people I have to thank for many reasons:

Adam Somlai-Fisher, Ailadi Cortelletti, Alberto Pezzotti, Alessandro Germinasi, Alessandro Masserdotti, Andrea Piccolo, Anna Capellini, Casey Reas, Chris Anderson, Claudio Moderini, Clementina Coppini, Concetta Capecchi, Csaba Waldhauser, Dario Buzzini, Dario Molinari, Dario Parravicini, Donata Piccolo, Edoardo Brambilla, Elisa Canducci, Fabio Violante, Fabio Zanola, Fabrizio Pignoloni, Flavio Mauri, Francesca Mocellin, Francesco Monico, Giorgio Olivero, Giovanna Gardi, Giovanni Battistini, Heather Martin, Jennifer Bove, Laura Dellamotta, Lorenzo Parravicini, Luca Rocco, Marco Baioni, Marco Eynard, Maria Teresa Longoni, Massimiliano Bolondi, Matteo Rivolta, Matthias Richter, Maurizio Pirola, Michael Thorpe, Natalia Jordan, Ombretta Banzi, Oreste Banzi, Oscar Zoggia, Pietro Dore, Prof Salvioni, Raffaella Ferrara, Renzo Giusti, Sandi Athanas, Sara Carpentieri, Sigrid Wiederhecker, Stefano Mirti, Ubi De Feo, Veronika Bucko.

We have verified the information in this book to the best of our ability, but you may find things that have changed (or even that we made mistakes!). As a reader of this book, you can help us to improve future editions by sending us your feedback. Please let us know about any errors, inaccuracies, misleading or confusing statements, and typos that you find anywhere in this book.

Please also let us know what we can do to make this book more useful to you. We take your comments seriously and will try to incorporate reasonable suggestions into future editions.

You can write to us at:

Maker Media 1005 Gravenstein Highway North Sebastopol, CA 95472 (800) 998-9938 (in the U.S. or Canada) (707) 829-0515 (international/local) (707) 829-0104 (fax)

Maker Media is a division of O’Reilly Media devoted entirely to the growing community of resourceful people who believe that if you can imagine it, you can make it. Consisting of MAKE magazine, CRAFT magazine, Maker Faire, as well as the Hacks, Make:Projects, and DIY Science book series, Maker Media encourages the Do-It-Yourself mentality by providing creative inspiration and instruction.

For more information about Maker Media, visit us online: MAKE www.makezine.com CRAFT: www.craftzine.com Maker Faire: www.makerfaire.com Hacks: www.hackszine.com

To comment on the book, send email to bookquestions@oreilly.com.

The O’Reilly web site for Getting Started with Arduino lists examples, errata, and plans for future editions. You can find this page at www.makezine.com/getstartedarduino.

For more information about this book and others, see the O’Reilly website: www.oreilly.com.

For more information about Arduino, including discussion forums and further documentation, see www.arduino.cc.

Preface ix

1 / Introduction

Arduino is an open source physical computing

platform based on a simple input/output

(I/O) board and a development environment

that implements the Processing language

(www.processing.org). Arduino can be used

to develop standalone interactive objects

or can be connected to software on your

computer (such as Flash, Processing, VVVV,

or Max/MSP). The boards can be assembled

by hand or purchased preassembled; the

open source IDE (Integrated Development

Environment) can be downloaded for free

from www.arduino.cc.

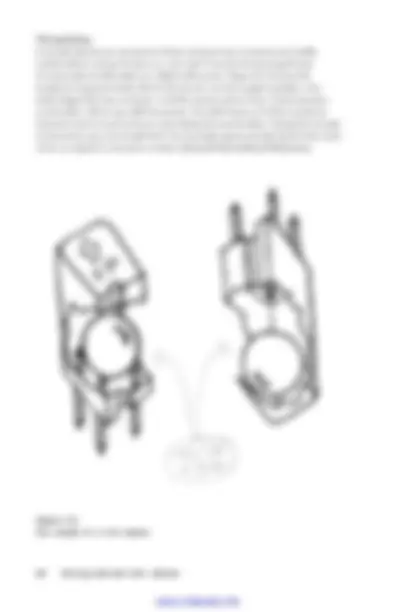

Arduino is different from other platforms on the market because of these features:

and Linux.

development environment used by artists and designers.

because many modern computers don’t have serial ports.

download the circuit diagram, buy all the components, and make your own, without paying anything to the makers of Arduino.

Introduction 1

2 Getting Started with Arduino

about US$35) and replacing a burnt-out chip on the board is easy and costs no more than €5 or US$4. So you can afford to make mistakes.

who can help you.

is therefore great for newcomers to get things working quickly.

This book is designed to help beginners understand what benefits they can get from learning how to use the Arduino platform and adopting its philosophy.

This book was written for the “original” Arduino users: designers and artists. Therefore, it tries to explain things in a way that might drive some engineers crazy. Actually, one of them called the introductory chapters of my first draft “fluff”. That’s precisely the point. Let’s face it: most engineers aren’t able to explain what they do to another engineer, let alone a regular human being. Let’s now delve deep into the fluff.

NOTE: Arduino builds upon the thesis work Hernando Barragan did on the Wiring platform while studying under Casey Reas and me at IDII Ivrea.

After Arduino started to become popular, I realised how experimenters, hobbyists, and hackers of all sorts were starting to use it to create beauti- ful and crazy objects. I realised that you’re all artists and designers in your own right, so this book is for you as well.

Arduino was born to teach Interaction Design, a design discipline that puts prototyping at the centre of its methodology. There are many defini- tions of Interaction Design, but the one that I prefer is:

Interaction Design is the design of any interactive experience.

In today’s world, Interaction Design is concerned with the creation of meaningful experiences between us (humans) and objects. It is a good way to explore the creation of beautiful—and maybe even contro- versial—experiences between us and technology. Interaction Design encourages design through an iterative process based on prototypes

2 / The Arduino Way

The Arduino philosophy is based on making

designs rather than talking about them. It is

a constant search for faster and more power-

ful ways to build better prototypes. We have

explored many prototyping techniques and

developed ways of thinking with our hands.

Classic engineering relies on a strict process for getting from A to B; the Arduino Way delights in the possibility of getting lost on the way and finding C instead.

This is the tinkering process that we are so fond of—playing with the medium in an open-ended way and finding the unexpected. In this search for ways to build better prototypes, we also selected a number of soft- ware packages that enable the process of constant manipulation of the software and hardware medium.

The next few sections present some philosophies, events, and pioneers that have inspired the Arduino Way.

The Arduino Way 5

Tinkering

We believe that it is essential to play with technology, exploring different possibilities directly on hardware and software—sometimes without a very defined goal.

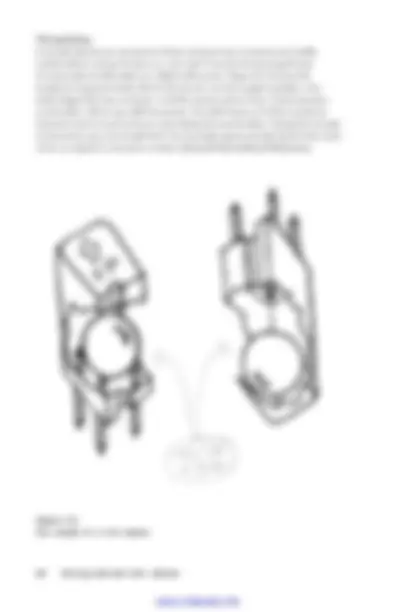

Reusing existing technology is one of the best ways of tinkering. Getting cheap toys or old discarded equipment and hacking them to make them do something new is one of the best ways to get to great results.

The Arduino Way 7

8 Getting Started with Arduino

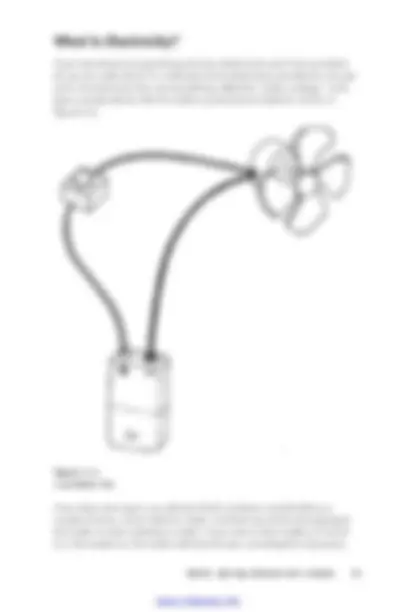

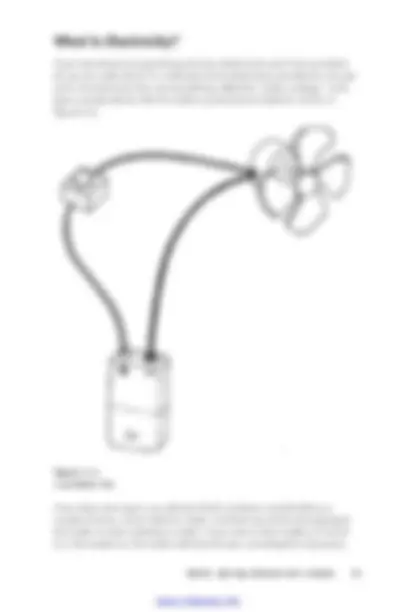

Patching

I have always been fascinated by modularity and the ability to build complex systems by connecting together simple devices. This process is very well represented by Robert Moog and his analogue synthesizers. Musicians constructed sounds, trying endless combinations by “patching together” different modules with cables. This approach made the synthesizer look like an old telephone switch, but combined with the numerous knobs, that was the perfect platform for tinkering with sound and innovating music. Moog described it as a process between “witnessing and discovering”. I’m sure most musicians at first didn’t know what all those hundreds of knobs did, but they tried and tried, refining their own style with no inter- ruptions in the flow.

Reducing the number of interruptions to the flow is very important for creativity—the more seamless the process, the more tinkering happens.

This technique has been translated into the world of software by “visual programming” environments like Max, Pure Data, or VVVV. These tools can be visualised as “boxes” for the different functionalities that they pro- vide, letting the user build “patches” by connecting these boxes together. These environments let the user experiment with programming without the constant interruption typical of the usual cycle: “type program, compile, damn—there is an error, fix error, compile, run”. If you are more visually minded, I recommend that you try them out.